Remittances 3.0: The undeployed secret weapon in the fight for universal energy access

Remittances is the single largest capital inflow into low and middle-income countries (LMICs). The article advocates for redirecting remittances from consumption to investment in home countries, particularly in the energy sector, and explores significant opportunities at this intersection.

Kumbirai Makanza

12/5/202311 min read

A lot of research, funding, politics and media attention focuses on the migration story. Often the discussion is centred around the chief causes; typically climate change, economic and political crises, and around the perilous journeys endured by migrants in search of a better life. Less attention however is paid to the second chapter of the story. This chapter describes how many migrants across generations have managed to integrate well into host societies, contribute to host economies, earn a decent living and manage to support their families back home through remittances.

As a first generation economic migrant in South Africa, I am no stranger to remittances. Coming from a middle income family, my remittances, commonly referred to as “black tax”, come in the form of a small monthly token of appreciation to my parents for the financial and emotional support which helped me become the person I am today. As my parents approach retirement age in Zimbabwe (which has a limited social safety net), my siblings’ and my remittances are increasingly becoming an important way in which to supplement their income. My situation differs from lower income households where remittances are a primary source of income and form a vital lifeline to enable families to buy food, basic goods, housing and education and health care.

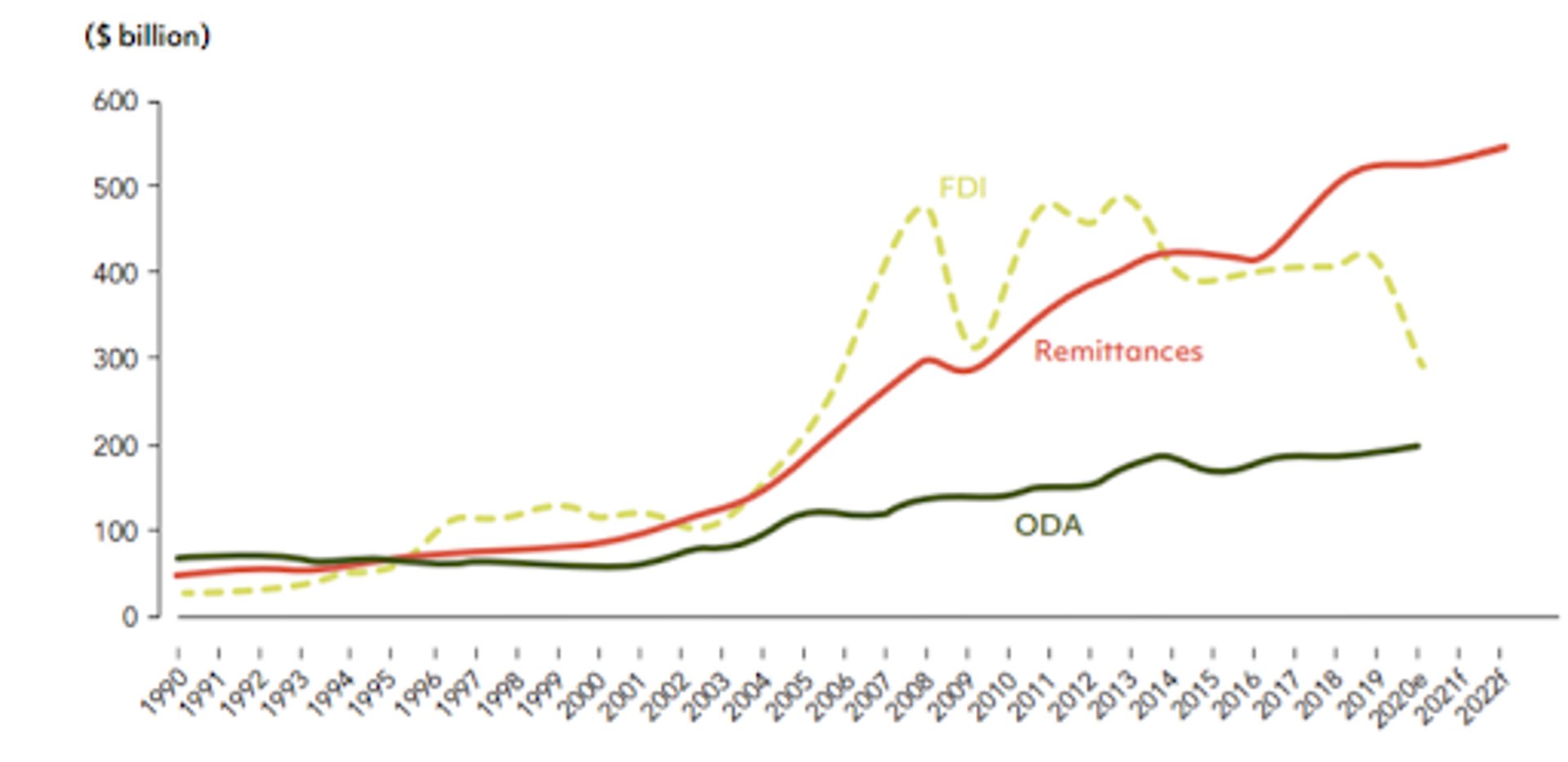

Unbeknownst to many, remittances are the single largest source of capital inflow into low and middle-income countries (LMICs). In 2020, remittances into LMICs (excluding China) exceeded the sum of foreign direct investment (FDI) and organisational development assistance (ODA). This number only accounts for formal remittances. According to the IMF unrecorded flows through informal channels are believed to be at least 50 percent larger than recorded flows.

Not only are remittances a massive source of capital inflow, they are also extraordinarily resilient. In April 2020, The World Bank-KNOMAD team projected a decline in remittance flows to LMICs by approximately 20% due to the predicted adverse impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on migrant worker employment and wages. They were wrong. Remittances defied this prediction with the latest data showing remittance flows fell by only 1.6 % to USD 540 billion in 2020. This was in stark contrast to the fall in FDI (excluding China) which fell by 30% in 2020 to $259 billion.

The power behind remittance and the source of its resilience is rooted in strong emotional family bonds. Migrants are willing to make sacrifices through cutting their own spending and drawing on their own savings in order to support their families back home. As a result, remittance flows tend to be more stable than other capital flows, and they tend to be countercyclical—increasing during economic downturns or after a natural disaster when private capital flows tend to decrease. Remittances have therefore become an important consumption smoothing mechanism for the recipient households and, as such, form an increasingly important (private) element of global social protection systems.

In addition to being resilient, remittances also tend to have a greater impact on target populations than other forms of capital. This is due to the fact that remittances are typically more precise than other forms of capital as they are targeted towards specific needs identified by recipients. This targeted approach has been shown to be more effective in reducing poverty relative to top down approaches. The trickle-down effect of FDI and ODA targeting marginalised populations in LMICs is often slow and imprecise, this is typically due to a combination of poor program design (often as consequence of a limited understanding of the local context), needless bureaucracy, high administration costs and wanton misappropriation of funds. Furthermore, remittances are more evenly distributed among developing economies than other forms of capital which often depend on other factors such as established trade links, bilateral relationships and previous colonial ties.

Despite being a well established form of capital transfer with stiff competition from a multitude of service providers, remittances remain complex and expensive. Traditional banks continue to maintain bureaucratic processes and high fees which fail to accommodate and cater to lower income groups, especially women and youth. International bank transfers continue to be dominated by the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) which is slow, expensive and antiquated. Alternatives to SWIFT, including INSTEX (European Union), CIPS (China), SPFS (Russia) and Ripple (private sector) and Stellar (private sector) have struggled to gain traction. However, there are positive signs of change and innovation driven primarily by specialised remittances companies, particularly through leveraging blockchain and mobile technologies. However this change is hampered by a lack of interoperability between different banks, mobile wallets and cryptocurrency wallets. Formal and informal cash remittances have been filling the void left by inefficient digital remittances. However, cash remittances are themselves also inefficient and expensive as they typically involve a series of intermediaries to complete a transaction.

In addition to inefficiencies and expenses, monetary remittances often suffer a great deal of leakages within families. This occurs when remitted funds are redirected to other purposes against the wishes of the individual remitting the funds. There are countless cases where remittances earmarked to build a house or start a business are syphoned off by family members through overcharging, under delivering or just outright theft. There are equally many cases where remittances designated to pay for a migrant's child’s education or healthcare are diverted for personal use by family intermediaries for unrelated expenditure like alcohol. Such cases create severe and at times irreversible strains on family relationships.

Governments taking notice

Remittances account for a significant part of foreign capital flows in developing countries. Remittances are considered to have a positive effect on the economy and can be beneficial for development. The beneficial impacts of remittances are particularly strong in countries where remittances are above 3% of GDP, where international reserves have a downward trend, or where external debt is rising. As a result governments with high remittance inflows around the world have taken notice and begun putting in measures to help spur an increase in the volume of remittances and to steer those remittances towards the government coffers and or towards public expenditure. One such measure is implementing a tax on remittances with the revenue being used for creating public goods. This however has been proven to be counterproductive, as imposing a tax on remittances could incentivize migrants to remit through informal channels or reduce the amount sent altogether. Another option is to impose mandatory remittance contributions. These were implemented by South Korea in the 1980s and Eritrea in 1993, where a requirement was set in place to donate a certain portion of remittances to the state. The success of this measure varied greatly depending on whether there was a strong sense of social obligation towards a country, which was not always the case and was particularly difficult to maintain in the long term. It is clear that an indirect approach to influence remittances through incentives is far more effective than taxes and mandatory contributions.

The evolution of remittances

While some remittances are channelled to household development projects, a significant percentage of remittances go towards household consumption. There is an opportunity to increase the dividend of remittances by shifting the pendulum away from consumption and towards investments in development projects that generate income. Investments have the potential to create resilient and sustainable income which is not dependent on the remitter’s capacity to continue earning income and sending money back home. This is an important step towards breaking the dependency syndrome among recipients.

Remittances need to evolve away from the current consumption-based remittance system and move towards sustainable investment solutions which bring long term value to loved ones and support development in home countries.

Monetary and goods and services remittances lose value over time due to leakages, inflation and depreciation. Productive assets and diaspora investment vehicles provide an alternative to the current frustrating, perpetual remittance expense cycle. Successful implementation of these investment models will bring some much needed development capital in LMICs, which in turn will empower individuals, communities and countries to become self-sustaining entities which create value. Sustainable development in LMICs will help stem human capital outflow and subsequently reduce the on-going “brain drain”.

The multi-billion dollar opportunity: Diaspora financed renewable energy investment models

Decisions to migrate are commonly due to a pursuit of well-being and better livelihoods. Mass migration events are often as a result of poor and deteriorating socioeconomic conditions in home countries or regions. Consequently, LMICs which depend heavily on remittances often have underdeveloped economies and energy sectors.

Another key driver of migration in the 21st century is Global Warming. Climate change is increasing the frequency of extreme weather events such as droughts, floods, wildfires and cyclones. These weather events create adverse economic shocks, from which many marginalised populations fail to recover in the absence of external support. Many who fail to recover from these shocks opt to move to regions where they feel there may be better economic opportunities. The Global South, home to a majority of LMICs, by virtue of its geography, has been disproportionately affected by climate change. LMICs are typically more vulnerable to climate change given their relatively high dependency on (subsistence) agriculture, limited social safety nets and limited capacity for effective climate adaptation at national level.

Access to clean and reliable energy has been proven to greatly improve income and quality of life. Energy is the ideal investment vehicle for remittances as it forms the foundation for the modern development that LMICs strive towards. Energy is a key enabler which unlocks a myriad of nascent commercial opportunities. Remittances already have an impact on energy consumption, albeit marginal. According to the research paper “The effect of remittance on energy consumption: Panel cointegration and dynamic causality analysis for South Asian countries”, there is evidence that a 1% increase in remittance income results in a 0.045% increase in energy consumption in the long run. However, there is no structured approach to systematically steer remittances into energy investments. A structured approach will amplify the economic and development outcomes of remittances.

As climate change disproportionately affects LMICs in the Global South, it is of paramount importance that remittances be invested in clean energy technologies. The viability of this investment strategy is supported by the fact that the Global South is naturally endowed with relatively high solar resource potential. Likewise, given the relationship between climate change and migration, there is a potential to blend climate finance and development aid to stem migration with remittances to invest in clean energy technologies which reduce carbon emissions and improve the economic conditions that were the reason for migration in the first place.

Unique market characteristics enabling renewable energy investments

Diasporans access to affordable credit in host countries.

Renewable energy projects are often characterised by a high initial capital expenditure relative to incumbent non-renewable technologies, offset over time by significantly lower operating costs. LMICs, businesses and families often do not have access to affordable capital to finance renewable energy projects. This is despite the fact that many of these projects are economically viable. The reluctance to invest in these projects stems from a combination of low incomes of the target populations, high perceived market risk and a poor understanding of local market dynamics.

In stark contrast, diasporans typically have higher levels of income and access to financial services relative to their families back home. Many diasporans are well integrated in financial systems and are eligible for credit at competitive interest rates based on their credit history and collateral assets in their host country.

There is a unique opportunity to leverage cheap credit available to diasporans in their host country to invest into renewable energy in LMICs. This will effectively reduce project cost of capital and shift exchange rate risk from financial institutions to diasporans. A diasporan may be willing to accept the exchange rate risk and take returns in local currency to meet their respective local obligations (for example as a means to substitute their remittances or to finance the construction of a retirement home).

Increasing levels of digital access, literacy and communication amongst diasporans and their families.

There are relatively high levels of digital access, literacy and communication amongst migrant populations and their respective families back home. The COVID-19 pandemic restrictions on movement have rapidly increased the digitisation and formalisation of remittances (as moving cash and goods across borders has become increasingly difficult).

There is a unique opportunity to create digital technology that leverages digital payments, social networks and remote monitoring to enable diaspora renewable energy investments.

Renewable energy business opportunities

Remittance 2.0 Goods and services remittances.

Renewable energy goods: Enabling diasporans to digitally purchase renewable energy technology on behalf of family members back home (or for their own use in their home country). Integrating the affordable credit available to diasporans into this model will help bridge the affordability gap, accelerating uptake, increasing potential market size and increasing average sale value. Integrating remote monitoring will help give diasporans greater visibility over the performance of a purchased asset, creating a digital connection and helping alleviate performance anxiety. There are businesses that have begun to occupy this space. UK start-up Umlilo Energy is an end-to-end service designed to enable Africans in the UK to seamlessly purchase, finance and install solar systems in their home country from anywhere in the world. Similarly, EDF recently launched “Diaspora Energy by EDF” with the aim to give members of the diaspora the opportunity to finance an off-grid solar system for their family, mainly in rural areas. According to EDF, its new platform guarantees its users a secure payment as well as delivery within a maximum of 15 days (for Ivory Coast).

Renewable energy services: Enabling diasporans to make direct digital payments for renewable energy services on behalf of family members back home. This can be employed for Pay-You-Go solar homes systems (SHS), mini-grid energy bills and utility bills

Remittance 3.0 Investment.

There are a wide range of renewable energy investment entry points for the diaspora, ranging from the individual to national level. Investment values can range in size from small investments that are nominal relative to a diasporan’s income to large scale investments which are core to a diasporans investment strategy. Additionally, the nature of the relationship with the beneficiary can vary from a close family member to projects which have impact in a country, region or community broadly. Investments can be made in the form of purchasing productive uses of energy assets and or through financing renewable energy assets/projects through mechanisms like crowdfunding or diaspora green bonds. Digital technology (digital payments, blockchain, social networks and remote monitoring) can be employed to efficiently market, aggregate, monitor and execute these investments.

Remittances 3.0 present a massive opportunity as an alternative to both remittance expenses and low interest savings (and investments) held by diasporans in host countries ($1 trillion+ in capital combined). It is believed that most migrants save as much money in the host country as they send home as remittances. According to the World Bank's Dilip Ratha, diaspora savings in host countries are estimated as high as $500 billion, of which a significant part is deposited in banks and credit unions, often earning very little interest. Providing secure, high impact investment vehicles would provide a compelling substitute to the low interest returns available in host countries.

Uniquely, if the diasporans are willing to receive returns in local currency in their respective home countries, this can reduce the exchange rate risk of international (foreign direct) investment.

Call to action

Remittance 3.0 presents the most exciting prospect in my opinion. The success of 3.0 will rely heavily on the ability to closely match an emotional connection to an investment opportunity. Diaspora Bonds were implemented most successfully in Israel. Development Corporation for Israel/Israel Bonds was first launched in 1951. Since then, investment into Israeli (diaspora) bonds has exceeded $44 billion. Proceeds from the sale of Israeli bonds have played a decisive role in Israel’s rapid evolution into a groundbreaking, global leader in high-tech, greentech and biotech. Israel has relatively strong government institutions and public trust. This differs from many LMICs where there is distrust in the government and its institutions. There is a strong perception of government mismanagement and corruption in many LMICs. This is particularly true amongst diasporans, many of whom are economic and political migrants whose decision to migrate is related to poor governance.

The focus of Next Century Power research is to better understand at which point on the Remittance 3.0 spectrum diasporans would be most willing to invest into renewable energy and to understand the characteristics of who would invest where. NCP's hypothesis is that diasporans in LMICs would be willing to invest large amounts of capital at individual family level and less so at national level given government mistrust. In addition, diasporans in LMICs would be willing to invest in local institutions (such as churches and schools) in home communities for which there are pre-existing emotional bonds. This phenomenon already exists. There are numerous examples of diaspora church groups “adopting” local congregations in home countries and helping them finance church expenses and projects, or examples of diaspora school alumni groups investing in new computer labs at local primary schools in their home country.

Developing effective Remittance 3.0 models is topical and of great importance at a time where diasporans are beginning to re-think remittances in their current form and as the private sector and governments look to build more effective economic bridges between the diaspora and their home countries.

Next Century Power would like to invite organisations, businesses, scholars and individuals with an interest in this topic to reach out and see how best we can collaborate and help bring the Remittance 3.0 revolution to life.

Contact us

Whether you have a request, a query, or want to work with us, use the form below to get in touch with our team.

Location

Siyapakanaka Consulting Private Limited

Plot 4790

Gaborone West Industrial

Gaborone

Botswana